Go here to read Madden’s review of Kearny’s March: The Epic Creation of the American West, 1846-1847 by Winston Groom

Recent Articles

An historian has declared that the three most written-about subjects of all time are Jesus, the Civil War, and the Titanic.

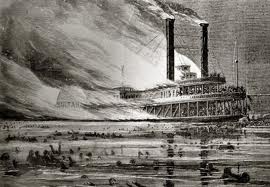

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912, the question arises, “Why can we not let go of that ‘tragic’ event?” April being also Civil War History Month, I am sadly reminded of the cruel irony of the fact that Americans little noted nor have long remembered the worst maritime disaster in United States history, the sinking of the SS Sultana, its losses greater than the Titanic, raising the question, “Why have we not taken hold of the Sultana?”

As our Coast Guard conducts its annual commemoration of the sinking of the Titanic, as London observes the centennial of that event, and as the movie Titanic returns to the screen in 3D to enthrall audiences worldwide, Americans, deep into the Civil War Sesquicentennial’s second year, are almost totally unmindful of the Sultana’s some 1,800 casualties–union soldiers, recently released from Andersonville and other Confederate prisons, and civilians, including women and children–who perished April 27, 1865 at 2 am, in darkness, in a cold rain, in the Mississippi River just above Memphis, as the assassinated President’s funeral train was crossing the United States.

An estimated 1,800 perished when the Sultana exploded, compared with the Titanic’s 1,523. More military passengers were from Ohio, 652, and Tennessee, 463, than from other states. About 800 survived, about 300 of whom later died of burns and exposure.

Among survivors who lived long lives afterward was Daniel Allen, from Sevier County, who testified in 1892, “I pressed toward the bow, passing many wounded sufferers, who piteously begged to be thrown overboard. I saw men, while attempting to escape, pitch down through the hatchway that was full of blue curling flames, or rush wildly from the vessel to death and destruction in the turbid waters below. I clambered upon the hurricane deck and with calmness and self-possession assisted others to escape.”

In my hometown Knoxville, in divided East Tennessee, the survivors met in April each year, including 1912, twelve days after the Titanic sank, until only one veteran showed up in 1930. July 4, 1916, survivors dedicated an impressive monument in Mount Olive Baptist Church Cemetery, 2500 Maryville Pike.

Writers have derived a plethora of meanings from the Titanic legacy, but in a very general context; the Civil War context for the unexamined symbolic relevance of the Sultana legacy is painfully specific, for as Shelby Foote said, “The Civil War is the cross-roads of our being as a nation.”

Despite the publication over the years of books about the Sultana, most Americans still have never heard of it. The first was Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors (1892) by Chester D. Berry, a survivor, (reprinted in 2005 by the University of Tennessee Press). Seventy years later James W. Elliott’s Transport To Disaster (1962) appeared; Jerry Potter, Memphis lawyer, published The Sultana Tragedy thirty years later. Not even Jim Brown’s excellent article in the News Sentinel two decades ago left a lasting impression on East Tennesseans.

But in 1987, Knoxville attorney Norman Shaw, not a descendant, started the Association of Sultana Descendants and Friends, whose newsletter is called Sultana Remembered. They have met annually in Knoxville, Memphis, Cincinnati, and other relevant cities.

The rest is silence.

No rich celebrities were among the estimated 2,400 passengers who boarded the Sultana, a boat built for only 376, over-loaded in a conspiracy of greedy civilian and military men. No iceberg-like external force ignited the explosion of four boilers known to be defective. No divers descend now to gaze upon a sea-preserved ship worthy of exhibition in replica at Dollywood, because the “Muddy” Mississippi shrugged its shoulders and moved into other channels, leaving the SS Sultana and its victims under mud where now a soybean field thrives.

The Prague Cemetery

By Umberto Eco

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $27, 444 pages

A review by David Madden

Far more than most novels ever, Umberto Eco’s “The Prague Cemetery” raises a plethora of questions, the primary one being, What moved Eco to construct this particular meshing of imagination and history?

A bestseller in Europe, the novel has earned a mixed response in the U. S.—praise and repugnance. Author of the world-famous medieval mystery thriller “The Name of the Rose,” Eco is known for his obsession, in popular fiction and in academic exercises, with language, puzzles, and conundrums that cause him to be labeled “playful.” Some forms of playfulness are inappropriate in public. Setting aside any wonder whether he himself is in any way anti-Semitic, is Eco having at least half as much fun, on the lowest level of his very being–spewing hatred of the Jews throughout his 444 pages–as his main character is?

Let us leap over such questions to a charitable interpretation teachable in graduate history seminars that dabble in fiction and in literature seminars that dabble in history, and come up with this high-minded answer in the form of another question: By involving his sinister main character in most of Europe’s major political events of the 19th century, does Eco, intentionally or unintentionally, make of him an embodiment of many of the evil forces behind those events?

The terrible people involved in the terrible events into which Eco immerses his readers, almost to the point of drowning, were real; but the main character, arch anti-anti-hero, is a creature of Eco’s fervid imagination. We know from experience and hearsay that taking a history course often does not take, so fine details of the wars of Italian unification and the terrors of the Paris Commune may prove quite repetitive and tedious for forgetful readers, but especially for those who know little or nothing beyond perhaps recognizing the name Garibaldi.

Tedious indeed are the seemingly endless details of the gluttonous experiences of the main narrator. A little less tiresome are the details of the conspiracies involving the narrator (who is or is not, or maybe may be two people, with a third narrator who probably is Eco, but not necessarily). He is a liar, fake, forger, murderer, betrayer, double-crosser, Jesuit hater, Mason hater, and, above all, a paranoid Jew hater whose rants might have tired even Hitler, but will assuredly nauseate a good many readers, while validating the firmly rooted prejudices of bigots who might, implausibly, read this quasi-novel.

Historically, Jew hatred was aroused and virulently sustained beyond the usual by the circulation in the 19th century of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” supposedly written by a cabal of rabbis who met in a cemetery in Prague to plan an eventual take-over of the world. It was actually a pastiche of passages from popular novels by Eugene Sue and Alexander Dumas. Our repulsive narrator participated with agents of the Secret Services of France, Germany, and Italy in circulating of that plan in crisscrossing contexts during threats of war and war itself.

Surely Eco knows that most citizens of the world in our time very well know that governments good and bad can be duplicitous, hypocritical, conniving, deceitful—the list is long, seldom balanced by a list of good attributes—and that anti-Semitism often serves their nefarious purposes. So in this novel, preachy by implication, what lessons, insights, visions is Eco offering us?

Damned if I know, damned if I don’t.

One faintly redeeming insight he may have prepared us to achieve on our own is that the schizoid narrator (writing his story at the suggestion of Doctor Freud) has over the years so submerged his ego and superego in false identities that he is now in anxiety over his lack of memory of the past and of self-awareness in the present.

But am I bending over backwards?

Founder of the US Civil War Center at LSU and Robert Penn Warren Professor Emeritus, David Madden has just finished his eleventh work of fiction, “London Bridge in Plague and Fire,” forthcoming in the fall.

Neufeld on Books

by Rob Neufeld

David Madden, master writer, shares fiction secrets

This past Tuesday, author David Madden laid out the secrets of good writing to an audience at Blue Ridge Books in Waynesville. It was a program version of his book, “Revising Fiction,” and a look ahead to the novel-writing workshop he’ll be inaugurating at the Black Mountain Inn, Feb. 20-25.

Many faces of words

“I met myself coming and going,” Madden recited, giving an example of a cliché that one might throw out, or transform into something good.

“A character could be truly thinking, ‘I met myself coming and going,’” he said, “and it could have profound implications.”

In Madden’s latest novel, “Abducted by Circumstance,” the phrase provides a shock of recognition to Carol Seaborg, who leads parallel lives. In one, she’s a housewife; and in the other, someone who has entered, through fantasy, the life of a woman whose abduction she witnessed.

“Abducted by Circumstance” is Madden’s tenth novel. He has also published dozens of other works, including plays and non-fiction. For 25 years, he served as writer-in-residence at Louisiana State University. Since moving to Black Mountain with his wife, Robbie, he has taught within the Appalachian State University and UNCA Great Smoky Mountains MFA programs.

For the sake of a comma

“Joseph Conrad,” Madden relates, “once came out of his study for lunch,” and answered his wife’s question about his morning accomplishments by exulting, “I put in a comma!”

After lunch, he went back to work and, when he came out for supper, his wife asked, “What did you achieve this afternoon, Joseph?” He proudly said, “I took the comma out.”

“That is what writing is all about,” Madden commented. “If I didn’t have anything else to say, that would say it. That’s what I mean by attention to everything.”

Sometimes, cutting words out in a revision process makes sentences truer, more powerful, and more mysterious.

Some of Madden’s favorite words and phrases to cut are: “It was,” “he said,” and “with.”

“She entered the room with a cape over her shoulders,” he narrated. “Why not: She entered the room, a cape over her shoulders. Take out the ‘with.’”

Regarding the sentence, “It was raining outside,” why is the word “outside” necessary? And what is “it”? Why not describe the way rain fell as an action?

Cutting out false and unnecessary words is a good goal for a first edit. It involves imagination, as does Madden’s other methods, including the uses of syntax.

Snap to it

“Impingement” is Madden’s term for stirring the imagination by having one statement lead suddenly to something quite different. The two ideas fuse, as in a molecular reaction.

For instance, there’s this line from Wright Morris’ novel, “Man and Boy”: “When he heard Mother’s feet on the stairs, Mr. Ormsby cracked her soft-boiled eggs and spooned them carefully into the heated cup.”

In this case, the impingement comes about because one thing causes the other. The sudden crack marks the place where the spark happens.

There are other ways to create the effect, such as when, in the same novel, cigarette smoke clears and the pigeons Mother saw through a window are replaced by a policeman. Pure magicianship— waving a cloak.

With the first example, the condensing of sentences creates the impression that Mother’s step actually cracks the eggs. There’s more kinetic energy in such a telling. It’s not only plots that have suspense; sentences do, too.

Energy is also the metaphor when Madden writes about the “charged image” in “Revising Fiction.” That book presents “185 practical techniques,” which not only include matters of style, but also: point of view; characters; narrative; dialogue; description; devices; and general considerations.

“A charged image,” Madden writes, is the “dominant image-nucleus in a story. As the reader moves from part to part, the charged image discharges its potency gradually. After the reader has fully experienced the story, fully perceived it in a picture, that focal image continues to discharge its electrical power.”

Pleasure is the rule of writing. One of Madden’s novels is called “Pleasure-Dome.”

For an example of the charged image in a novel, Madden points to “Don Quixote” by Cervantes. The scene in which Don Quixote and Sancho Panza approach the windmills is “only a page and a half in a book of about a thousand pages,” Madden notes; yet “it is probably the best-known image from fiction worldwide.”

In his workshops, Madden teaches through direct work with writers, rather than by circulating copies of drafts and having other students critique. “The art of writing,” Madden says, quoting Sean O’Faolain, “is rewriting.”

Rob Neufeld writes the weekly book feature for the Sunday Citizen-Times. He is the author and editor of five books, and the publisher of the website, “The Read on WNC.” He can be reached at [email protected] and 505-1973.

ABOUT THE WORKSHOP

The Black Mountain Inn inaugurates David Madden’s “Black Mountain Novel Workshop,” February 20-25. Admission is limited to five serious writers who have finished a novel that Madden considers publishable, but that needs revision. Sessions last three hours in the morning and three hours in the afternoon. Members of the workshop stay in the five rooms of the Black Mountain Inn, which will provide all meals. Submit a complete novel, minimum length 250 double-spaced pages, unbound, to David Madden, 118 Church St., Black Mountain. Manuscripts will not be returned. Submission deadline is February 1. Participants will be chosen February10. For further information call 669-2757, or visit davidmadden.net.

MORE

The book:

“Revising Fiction: A Handbook for Writers” by David Madden (New American Library, 1988).

Madden’s new novel:

“London Bridge in Plague and Fire,” due out this summer. Visit davidmadden.net.

See videos of Madden on style; and about a favorite book on “The Read on WNC,” www.thereadonwnc.ning.com.

ART

David Madden

The following review appeared in the December 2011 issue of CHOICE

Wright Morris territory: a treasury of work, ed. by David Madden with Alicia Christensen. Nebraska, 2011. 306p bibl afp ISBN 9780803236585 pbk, $19.95

A prodigious and prolific writer (and exceptional photographer), Morris (1910-98) will likely remain one of the US’s most significant 20th-century literary voices. A considerable body of scholarship already exists on his work–fiction and nonfiction–but this is the first Morris reader. Although much of Morris’s work is grounded and steeped in region, specifically the Great Plains, Madden (emer., Louisiana State Univ.) states in his excellent introduction that Morris is not a “regionalist” as such (i.e., a “Nebraska writer” or “writer of the Great Plains”). Like other American writers devoted to place–Willa Cather and William Faulkner, for instance–Morris captures the ethos of the region but also transcends it; in both fiction and nonfiction, Morris’s subjects, style, range, and insights into human condition appeal to a wide audience. Prefaced with a fine biographical sketch by Joseph Wydeven as well as Madden’s introduction, and supplemented with Morris’s photographs, this reader will cultivate a much-deserved wider audience for Morris. Madden was wise in organizing the material not by chronology or by theme but rather by “juxtaposition,” offering readers–both those familiar with Morris and those new to him–a unique, refreshing approach to understanding and appreciating his considerable range and artistry. Summing Up: Recommended. Lower- and upper-division undergraduates; general readers. — K. L. Cole, University of Sioux Falls

Novelist returns to scene of fictional crime: Thousand Islands in winter

By CHRIS BROCK

Watertown Daily Times

SUNDAY, JUNE 27, 2010